WomensHistoryReads interview: Mary Sharratt

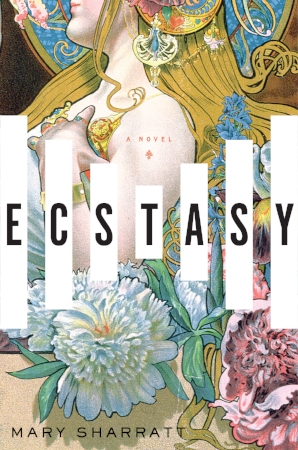

I've been waiting what seems like forever to talk about Mary Sharratt's latest novel ECSTASY, which follows Alma Mahler's extraordinary life in turn-of-the-20th-century Vienna. I heard Mary speak about this book on a panel last June at the Historical Novel Society Conference and was instantly entranced. Then I managed to get my hands on an ARC and was blown away both by the gorgeous cover and the story within. And now the book is finally coming out -- tomorrow! So grab your copy ASAP. You'll be riveted by the tale of this talented, brilliant woman who was truly ahead of her time.

Mary Sharratt

Greer: Tell us about a woman from the past who has inspired your writing.

Mary: From my first novel Summit Avenue, published in 2000, I have always written historical fiction centered on strong women. But I didn’t write my first work of biographical fiction about a real life historical woman until my 2010 novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill. The inspiration arose when I moved to the Pendle region of Lancashire in Northern England where the true story of the Pendle Witches of 1612 literally cast their spell on me and changed me forever.

In 1612, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest were hanged for witchcraft. But the most notorious of the accused, Bess Southerns, aka Old Demdike, cheated the hangman by dying in prison before she could even come to trial. This is how court clerk Thomas Potts describes her in The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knowes ... Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no man escaped her, or her Furies.

Not bad for an eighty-year-old lady. Once I read this, I fell in love. I simply had to write a book about this amazing woman. Bess became the guiding voice and power behind my novel.

Reading the trial transcripts against the grain, I was astounded how her strength of character blazed forth in the document written to vilify her. She freely admitted to being a healer and a cunning woman, and she instructed her daughter and granddaughter in the ways of magic. Her neighbors called on her to cure their children and their cattle. What fascinated me was not that Bess was arrested on witchcraft charges but that the authorities turned on her only near the end of her long, productive career. She practiced her craft for decades before anybody dared to interfere with her.

Greer: What’s your next book about and when will we see it?

Mary: My new novel Ecstasy, released on April 10, is drawn from the dramatic life of Alma Schindler Mahler (1879-1964), one of the most controversial women in the twentieth century. Her husbands and lovers included composer Gustav Mahler, Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius, artist Oskar Kokoschka, and poet Franz Werfel. Yet no man could ever claim to possess her. She was her own woman to the last, polyamorous long before it was cool, and a composer in her own right. Sadly most commentators, including some of her own biographers, focus not on her talent or creativity but instead bemoan how she “failed” to be the ideal woman for the great men in her life. Alma, like Lilith, was a strong and independently-minded woman who claimed full expression of her sexuality only to be demonized as a man-destroying monster. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s observation that well-behaved women seldom make history could have been written about Alma.

Coming of age in the glittering artistic hotbed of turn-of-the-twentieth century Vienna, young Alma Maria Schindler was a most accomplished pianist—her teacher thought she was good enough to study at the Vienna Conservatory. However, Alma didn’t want a career of public performance. Instead she yearned to be a composer. Her lieder, composed under the guidance of her mentor and lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, are arresting, emotional, and highly original and can be compared with the early work of Zemlinsky’s other famous student, Arnold Schoenberg.

But the odds were stacked against her. In turn-of-the-twentieth century Vienna, women who strived for a livelihood in the arts were mocked as the “third sex”—the fate of Alma’s friend, the sculptor Ilse Conrat. When a towering genius like Gustav Mahler asked Alma to give up her composing career as a condition of their marriage, she reluctantly succumbed.

Yet underneath it all she was still that questing young woman who yearned to compose symphonies and operas. Shortly before her marriage, twenty-two-year-old Alma wrote in her diary, “I have two souls: I know it.” Born in an era that struggled to recognize women as full-fledged human beings, Alma experienced a fundamental split in her psyche—the rift between herself as a distinct creative individual and herself as an object of male desire. The suppression of her true self to become the woman Mahler wanted her to be was unsustainable and inhuman. Eventually the authentic Alma erupted out of this false persona.

What emerged was a woman far ahead of her time, who rejected the shackles of condoned feminine behavior and insisted on her sexual and creative freedom. Alma eventually returned to composing and went on to publish fourteen of her songs. Three other lieder have been discovered posthumously. Now her work is regularly performed and recorded.

Alma was not only a composer but what in German is called a Lebenskünstlerin, or life artist—she pioneered new ways of being as a woman that was in itself a work of art.

Greer:What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

Mary: I’m on a mission to write women back into history and I find this both exhilarating and daunting. To a large extent, women have been written out of history. Their lives and deeds have become lost to us. To uncover the buried histories of women, we historical novelists must act as detectives, studying the sparse clues that have been handed down to us. To create engaging and nuanced portraits of women in history, we must learn to read between the lines and fill in the blanks.

At its best, historical fiction can play a crucial role in writing women back into history and challenging our misperceptions about women in the past.

Unfortunately we, as writers, can run into problems when we present a view of historical women that challenges common misperceptions. On the one hand, readers and critics are justifiably skeptical about novelists who present plucky historical heroines with attitudes that feel too contemporary and thus anachronistic to their time and place. On the other hand, if you sit down and do the research, you will discover that every epoch had its radical voices, movers and shakers, extraordinary women who rocked the establishment. Think of Sappho, Hypatia, Hildegard of Bingen, Elizabeth I of England, Aphra Behn, Anne Bonny the Pirate Queen, Emma Goldman, and Rosa Parks, to name a few. Too often readers and, unfortunately some reviewers, appear to have a distorted and uninformed view of women in history and seem too quick to label any strong heroine anachronistic, even if the author has backed up the fiction with considerable research.

My hope is that as more authors delve into the lives of historical women and present them in all their nuanced glory, public perceptions on women’s history will undergo a long overdue sea change.

My question for Greer: Play matchmaker: what unsung woman from history would you most like to read a book about, and who should write it?

Greer: I've asked so many people this question and enjoyed all their answers -- and I can't believe I didn't think ahead to come up with an answer of my own!

I found out just last year that the much-heralded Wright Brothers, Orville and Wilbur, had a much-less-heralded sister, Katharine! (And please don't judge me when I admit that I found this out from the TV show "Drunk History," which actually does a great job of digging up interesting lesser-known figures, many of them women who deserve more time in the spotlight.) While the role she played in facilitating their success was definitely a supporting role, one could argue that they wouldn't have been able to get their venture off the ground (as it were) without her. Yet after years and years supporting her brothers, when she struck up a romance with an old beau, Orville stopped speaking to her entirely, and only came to visit her on her deathbed. There are some nonfiction accounts that speak to the facts of her life, but I think what she really needs is a juicy emotional epic that explores her thoughts, fears, joys and sorrows. And nobody does a juicy emotional epic like Ariel Lawhon (whose I Was Anastasia just came out a couple weeks back, and is totally a must-read.)

Read more about Mary and her books at marysharratt.com.

(And of course, keep checking back here daily for more installments of #WomensHistoryReads!)